During one particularly dank and grey day between Christmas and New Year, for want of nothing better to do I decided on an impromptu road trip, and hastily found the last available room at a traditional country inn off the beaten track in Northumberland (on the edge of Kielder Forest to be precise). I had passed by Kielder many times on trips up to Scotland previously up the spectacular A68 but had never stopped to explore.

The overnight stop, Holly Bush Inn at Greenhaugh, had an open fire, good food and a fine selection of beers, so all was well. And it was one beer in particular that caught my attention… Sycamore Gap. But more on that later.

During one particularly dank and grey day between Christmas and New Year, for want of nothing better to do I decided on an impromptu road trip, and hastily found the last available room at a traditional country inn off the beaten track in Northumberland (on the edge of Kielder Forest to be precise). I had passed by Kielder many times on trips up to Scotland previously up the spectacular A68 but had never stopped to explore.

The overnight stop, Holly Bush Inn at Greenhaugh, had an open fire, good food and a fine selection of beers, so all was well. And it was one beer in particular that caught my attention… Sycamore Gap. But more on that later.

Forestry England purchased the land with public money in the mid-20s and was briefed with providing a strategic and sustainable source of timber for industry and house building. The tree planting comprises of 95% conifers, with a small population of broadleaves including birch, rowan cherry, oak, beech, and willow. This sole purpose of planting trees purely as a resource carried on up to the 1960s, until awareness of environmental needs, as well as the benefit of additional amenity space became more widely understood and appreciated.

Reforestation has been around for thousands of years. Roman records dated 149 B.C mention the planting of conifers for ship timber, and before that, possibly as early as 1000 B.C. the Zhou empire in China created an official Forest Service. More recently, from about the 16th Century, landowners in Britain and across Europe created timber plantations to supply timber for ship building and later, other industries.

All of this tree planting, although on the surface an ideal way to offset our carbon footprint throughout the years, was really just tree planting to provide a product source, rather than replacing the native forests like for like. Ecological reforestation, in other words re-establishing forests back to their similar state, has only come to the fore fairly recently.

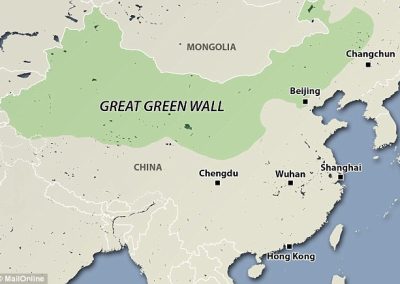

Today tree planting is more popular than it ever has been in an attempt to slow down or even balance out the effects of mankind’s carbon emissions, but trees also have so many more benefits. They attenuate water, helping to stop flooding, stabilise ground and provide crucial wildlife habitats. This is on top of the shelter they can provide from the elements, or even halting the advancement of hostile natural conditions. In the case of China’s Great Green Wall – https://earth.org/what-is-the-great-green-wall-in-china/ – a 70-year reforestation program aims to stop the ever-advancing Gobi Desert, by creating a swathe of man-made forest covering 88 million acres in a “green wall” stretching 3,000 miles by 900 miles wide in some places.

China is also supporting a similar project in Africa – https://www.greatgreenwall.org – The “Great Green Wall” of Africa will eventually stretch right across the central Sahel belt at the southern edge of the Sahara, bringing shelter, drought alleviation, food security and more importantly, jobs and a reason for people to stay, slowing the mass migration of the population.

Here in the UK, we are one of the least wooded countries in Europe with only 13% canopy cover, compared with Germany (32%) and France (31%). In 2018 approximately 1,400 hectares were planted against a government target of 5,000 hectares, equating to less than £1 per person per year.

There are many reasons for deforestation in the UK. As mentioned earlier, going back centuries we needed timber for our Navy, then there was the industrial revolution, then World War 1. Another huge impact on our forests and woodlands was intensive agriculture during the mid-20th Century, with farming policy focused on food production. Compared to agriculture, there was little attraction in growing trees, which involve high upfront costs for a slow-growing commodity, which may take decades to provide any financial return.

Coincidentally, only a few weeks ago (6th January 2022), it was announced that the Government is planning to incentivise farmers in England to rewild vast areas of land between 500 – 5,000 hectares, turning it over to wildlife restoration, carbon sequestration and flood prevention. There are also plans for an additional Local Nature Recovery Scheme aimed at smaller scale environmental improvements, such as the creation of wildlife habitats, tree planting (ideally native), as well as the restoration of peat and wetlands. The aim is by 2042 to have restored (up to) 300,000 hectares of wildlife habitat.

In 1919, the Forestry Commission was created to not only reforest what was lost, but to formulate a planned program of monoculture tree planting to provide a national resource to meet future demands. Then some fifty years later in 1972, the Woodland Trust was set up. As the UK’s largest woodland conservation charity, its primary objectives are the creation, protection, and restoration of our native rather than resource driven, woodland heritage. To date The Woodland Trust has planted over 50 million trees.

Many large-scale reforestation initiatives focus on quantity, and many people automatically think of reforestation as the monoculture forestry projects in the Highlands or National Parks – hillsides covered with tens of thousands of conifers, in a constant cycle of cutting and replanting. This type of forestry is a vital part of our timber supply chain and here at Green-tech it is a huge and very important part of our business. With all the necessary stakes, tree guards, spirals, and other products critical to successful tree planting, we hope to play our part in helping to plant around 10 million trees in the current 21/22 season.

However, when does reforestation become forest restoration?

Mongabay.com, a non-profit conservation news platform defines reforestation as, “planting trees to restock depleted or clear-cut forests, regardless of whether the resulting landscape is a monoculture plantation or a biodiverse forest ecosystem”.

Whereas forest restoration is, “actively attempting to return an area to its previous naturally forested state; the priority is the recovery of a forest ecosystem, not just tree cover.”

In rural areas, native broadleaf woodland species are usually more desirable from an environmental aspect than the timber producing conifers. By restoring our forests and woodland to the way that it was benefits not only the wildlife that evolved to depend on these tree species, but also to the ground that they stand in. For example, planting conifers in peatland, bogs, and moorland in the 80s actually damaged the environment. The trees absorbed most of the water available and dried out the soil, affecting the peat’s natural ability to sequester carbon. Quite simply, nature never intended for these particular trees to be there. Varying the species also means they are less vulnerable to disease than monocultures.

There are many other smaller, but just as important forest or woodland restoration projects that are taking place all over the UK. One such project is the 347-hectare Heartwood Forest in Hertfordshire – https://heartwood.woodlandtrust.org.uk – planted by the Woodland Trust. This new forest consists of more than half a million native trees, pockets of ancient bluebell woodland, hedgerows, and wildflower meadows, all on what was not so long-ago agricultural land. Heartwood is now England’s largest continuous new native forest.

So, there is a valid requirement for both reforestation, supplying us with an ongoing source of timber, and forest restoration, keeping as many of our native trees true to their natural habitat and geographical/geological location.

The UK Forestry Standard (UKFS) is the reference standard for sustainable forest management across the UK and clearly states that conservation of biodiversity is an essential part of sustainable forest management. It is vital in maintaining environmental functions such as climate regulation and soil conservation in addition to biodiversity and wildlife habitats.

“By providing these important ecosystem services, biologically diverse forests and woodlands also contribute to the sustainability of the wider landscape.”

“How did that tree get there?”

If we go back to the Sycamore Gap beer – the tree in question is not just a nice image chosen at random for a beer label. It is an actual tree, quite a famous one by all accounts (as featured Kevin Costner’s Robin Hood), and claimed to be the most photographed tree in Britain. It sits in a dip between two rocky outcrops somewhere along the nearby Hadrian’s Wall. Obviously, ever the explorer, I set out on a mission to find it.

The fact that 2,000 years ago, someone built a wall from coast to coast fascinates me; my wife Louise, she’s not so keen. So, the prospect of getting out of a perfectly warm car to traipse three miles up and down hills to look at a tree in a wall was met with some reluctance.

But traipse we did, and for my efforts I was rewarded with my ideal shot!

As an aside, the Sycamore is thought to have been introduced into Britain by the Romans, which seems quite fitting.